Money, banking, and commerce thrived in ancient Mesopotamia, in which some of the earliest known codified systems of financial laws arose. Mesopotamians used monetary denominations of talents, minas, and shekels, which spread throughout the adjoining realms. Assyrians and Babylonians also became well-acquainted with gold: They cast large-denomination gold bars weighing around 30 pounds, the larger gold bars stamped with images of lions, the smaller bars stamped with images of ducks. However, the earliest market economies appear to have arisen through the use of commodity money which was originally based on grains: the Mesopotamian currency known as the shekel was not originally a coin, but a measure of weight for quantifying barley. Moving forward from these early origins, money and commerce flourished, and famed cities such as Babylon became renowned for their wealth, as well as being among the earliest known birthplaces of banking, money-lending at interest, and profit-seeking by large business enterprises.

Origins of Ancient Mesopotamian Money

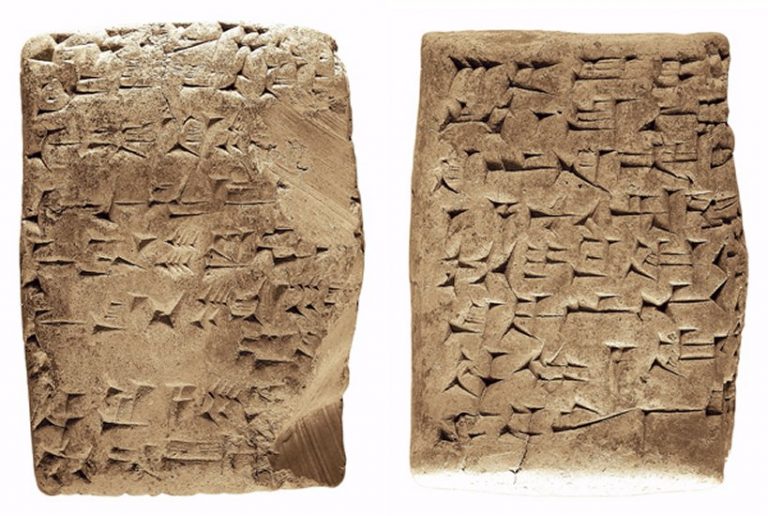

Prior to the introduction of coinage, the ancient Mesopotamians had developed a system in which clay tokens carved in the shape of various commodities were used in the markets. These could be exchanged much more easily than the actual crops, livestock, and other physical commodities that they represented, which would be physically delivered only after negotiations concluded using the tokens. To combat the counterfeiting of the clay tokens by unscrupulous individuals who did not actually possess the underlying physical goods, the tokens began to be sealed in clay pots stamped with the owner’s seal. This was later further simplified to a system in which the tokens were discontinued, and the symbols alone were stamped on clay tablets.

As early Mesopotamian markets grew and a large array of goods and services were available on the markets, grains were chosen as an early form of commodity money to serve as a unit of account, and the ancient shekel coin represented a standardized measure of weight for grain money (barley) held in security at the granary. The Mesopotamian granaries have consequently been said to be the ancient predecessors of banks and insurance companies.

The Temple Bankers of Babylon

Old-time connections exist between temples and banking in many realms: Ancient Babylonian, Grecian, Roman, and Egyptian temples all appear to have served as centers of operations for money-lenders, and were key financial centers in major cities. The Babylonian Temple Bankers stand out as some of the earliest known exemplars of such practices.

Both temples and palaces were used as strongholds for storing money, treasure and commodities, but the Temples were the first known creditors to profit from charging interest and rent on their assets and properties. The Babylonian Temple Bankers are credited with having legitimized the concepts of profit-seeking behavior and interest-bearing debts. The temple money lenders loaned money to both individuals and sovereigns, charging some designated rate of interest as compensation. As early as 2000 BC, some Babylonians were reportedly required to pay as much as a sixth of their deposit for the privilege of depositing their gold in the palatial and temple treasure houses, both of which loaned money and charged interest.

Banking & Financial Regulations of the Ancient World

The early law codes of Sumer are believed to have been among the earliest known codes of written financial laws, and the Babylonian legal code developed a detailed system of prices based on various commodities. Some of these elements are still in use in modern systems, such as interest rates, fines for financial malfeasance, and laws governing taxation or the division of property.

Writing tablets discovered in the ancient ruins have provided a wealth of evidence attesting to money and finance in ancient Babylon: Hundreds of thousands of stone cuneiform blocks have been unearthed from the ruins, including many which record the financial transactions of ancient Babylonian merchants and bankers. Some historians speculate that ancient Mesopotamian writing systems may even have originated from these financial accounting methods, as in the Mesopotamian city of Uruk, where the earliest known writings are bookkeeping entries.

Among the earliest recorded loans were grain loans made to farmers and traders around 2000 BC, in Assyia and Babylonia. By the time the Code of Hammurabi was set in stone on a seven foot stone block (circa 1750-1760 BC) and copied onto numerous other stone tablets, the banking industry was already so well-evolved that the government sought to regulate it, along with the activities of wealthy landowners.

Babylonian Businessmen: The Grandsons of Egibi and the Sons of Maraschu

Most of the oldest Bablyonian banking firms are not known by name, but some of the ancient cuneiform records attest to the long legacy of a 7th century BC banking and pawnbroking firm known as The Grandsons of Egibi. The trades of banking and pawnbroking were often practiced together in earlier periods, along with money-changing. The ancient records indicate that the Gransons of Egibi made loans and accepted deposits, that they invested and speculated to earn a profit, and that they owned ships used in trading voyages.

Another ancient firm, The Sons of Maraschu based in Nippur, apparently offered similar banking services in addition to their trade as goldsmiths and jewelers. They evidently also specialized in leasing and renting properties. Among the array of services they provided for profit were the tax-farming of wealthy estates, the renting of fish-ponds, city financing of infrastructure projects and waterworks, and the sale and distribution of beer.